Japan in 1989, China in 2023, India in 2024: the year that governments in these countries officially started to worry about falling birth rates.

Fewer babies seems like a strange thing to be concerned about in India, a country of 1.4 billion people. We are reminded of the fact that we are the world's most populous country every time we step into a Mumbai local, a Bangalore metro; if we enter a mall during a Diwali sale, or misguidedly visit Shimla on a long weekend.

But fewer numbers of babies worry governments due to the economic impact. A falling birth rate means a shrinking working population, slower GDP growth and lower tax payments to governments to fund old age pensions, subsidies, and social security. So when working populations fall, the country becomes poorer over time.

For a population to be at replacement level and neither grow nor shrink, a country needs a fertility rate (average number of children per woman) of 2.1. India's population fell below that fertility replacement level in 2020. And the fertlity rate is even lower in southern states like Kerala, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, where the average number of children per woman is between 1.2 and 1.6. The Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu M K Stalin has suggested that to fix this, Tamilians "should have 16 children each".

Humans used to be a fertile species - fertility rates typically used to be between 4.5 to 7.5. But we are now at a turning point. For the first time in recorded history, the world's largest economies are all below the population replacement rate.

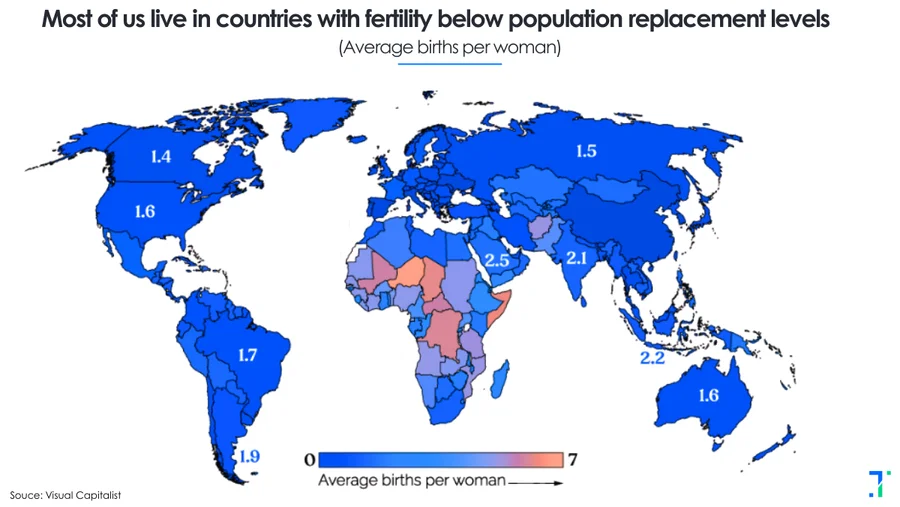

Most of Europe fell below the replacement level in the 1970s, the US in the 1980s, and China in the 1990s. South Korea’s fertility rate fell below 0.7 children per woman this year, the lowest in the world, meaning its population will halve by 2075. Africa is now the only large region in the world with fertility rates above the global replacement level.

Most of the world's economic output now comes from low-fertility countries. Economists have started to panic, over this output falling as populations decline.

In the 1960s, the writer Paul Ehrlich visited India and, overwhelmed by the sheer number of people in the streets of New Delhi, warned about over-population disaster and global famine. Decades later, the Cato Institute called Ehrlich "a misanthrope who'd make you apply for a government permit to have a baby if he could".

Now we are worrying about the opposite: too few people. But is a declining population really that bad for the world?

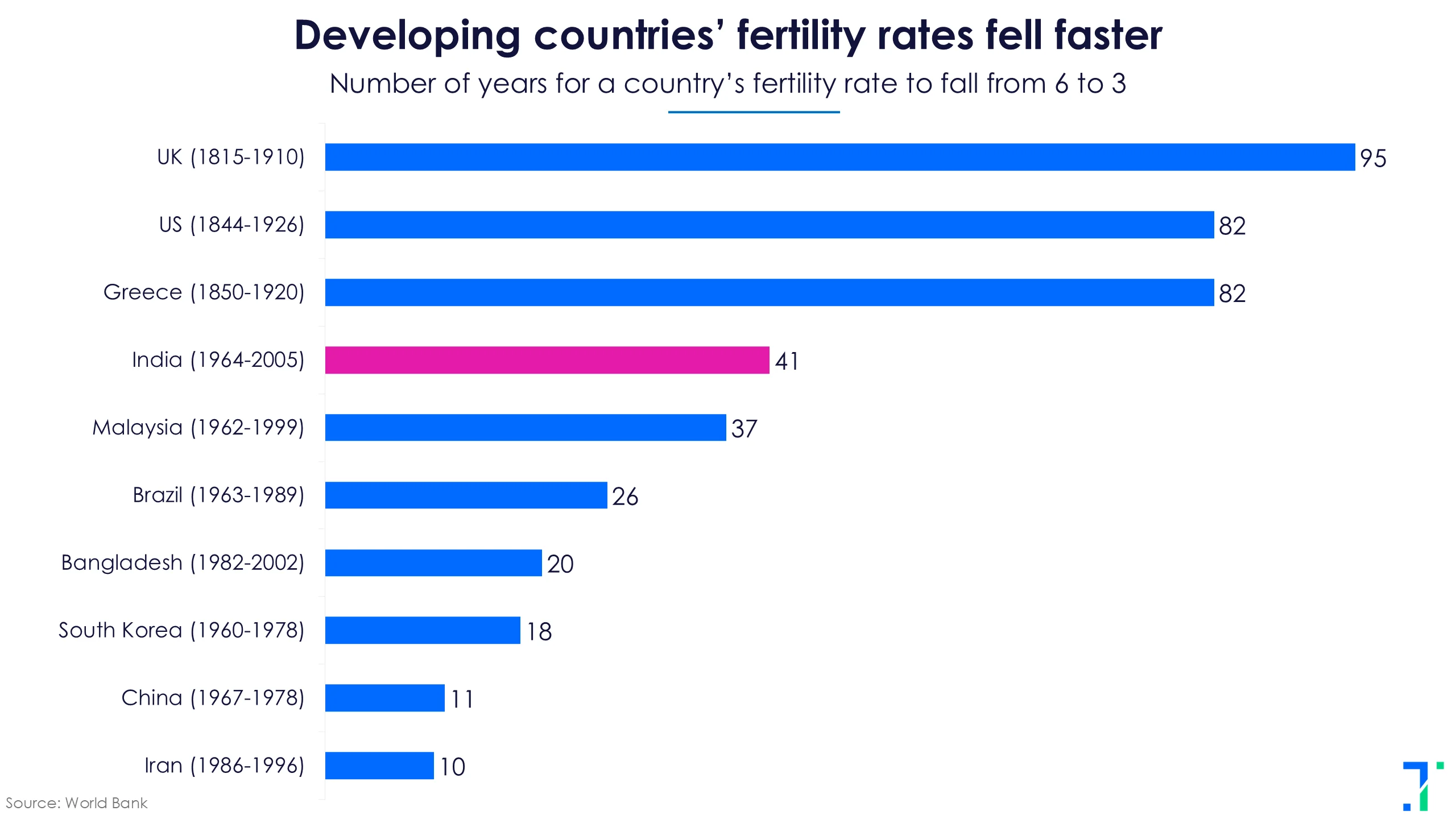

Fertility is not just falling - it is falling faster than before

When I walk around my city (Bangalore), an interesting trend I see is the number of families with just one kid. Just a few years ago, two kids was common enough. Now among friends and family, I am seeing a lot of ones - and even a few zeroes.

This trend is happening worldwide. Fertility is falling faster than before. The decline from a fertility rate of six to three took almost a century to happen in Britain—from 1816 to 1910. It took less than half that time for India, just 18 years in South Korea and 11 years in China.

In cities like Seoul and Beijing, nursery school staff are taking up jobs in old age homes instead. More than 10% of pre-school teachers in China have quit in the past five years due to falling student numbers.

When people are asked about why they are having fewer children, they mention the high cost of living, lack of time, and a lack of community support because in many cases, parents live as nuclear families while their relatives live elsewhere.

But when governments have tried to intervene by providing paid time off for parents, free childcare and generous child subsidies (China is offering couples $500 a year to have a child), the fertility rate has not increased.

This suggests that there are other factors at work. Economists have for instance, found a direct relationship between the number of years of education women receive, and falling fertility levels. When women have options like jobs and access to birth control, they have fewer kids.

Children also once used to be the only social security people had in their old age. But they take time and money to raise. They are also unpredictable: as adults, they may move far away from you, marry someone you don't like, or even change their minds about you. In the age of investments with predictable returns, reliable careers and pensions, having kids has become increasingly optional.

Are we having another Ehrlich moment?

Is it possible, that like Paul Ehrlich, we are panicking prematurely? In 1900, the world's population was around 1.6 billion. We are sitting at four times that number, as populations across the globe exploded in the past 100 years.

When population soared, technology - in the form of fertilizers and pesticides that raised crop yields - saved humans from the famine Ehrlich predicted would "end the world in 2000". Now, technology is again changing fast.

Better healthcare is already helping people to have longer careers - CEOs like Warren Buffett are working at 94, which would have been unthinkable even two decades ago. As people live longer and healthier, retirement ages can be pushed, putting less stress on pensions and social security. Rather than worry about ageing populations, countries should worry about populations ageing well.

Another factor is the underemployment of women in countries like India. Increasing labor participation of women from the current 40% levels would provide a long-term productivity boost, rather than falling for bad ideas like pushing them back home to have sixteen children.

AI is a third new, important factor to consider - if artificial intelligence and robots substantially raise productivity per person, then countries will be able to drive economic growth with much fewer people. And if AI is eventually able to innovate at human or close to human levels, then we will start seeing technological breakthroughs at an even faster pace than ever before.

Falling fertility has coincided with huge gains for us in gender equality, education and reproductive freedom. Rather than trying to rewind the clock, we should think about how we can build a world with fewer people. The planet will thank us.