It’s that time of the year again, when the sky above a tiny mountain town is filled with the sound of helicopters and private jets, as global CEOs, diplomats and political leaders descend on Davos in their best business suits.

Typically, the events are glorified pitch decks, where countries sell their growth stories and sign deals that government leaders hope to turn into factories and jobs on the ground.

But this is not a typical year.

Canadian PM Mark Carney put it bluntly: “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition.” Globalization and open trade patterns are breaking down as US foreign policy has become hostile, and as Donald Trump imposes tariffs and demands territory and natural resources that belong to other nations.

That’s why almost every country in Davos this year will pitch harder than usual, fighting for a slice of whatever markets are still available. India has sent its largest-ever delegation as it eyes more access and trade deals.

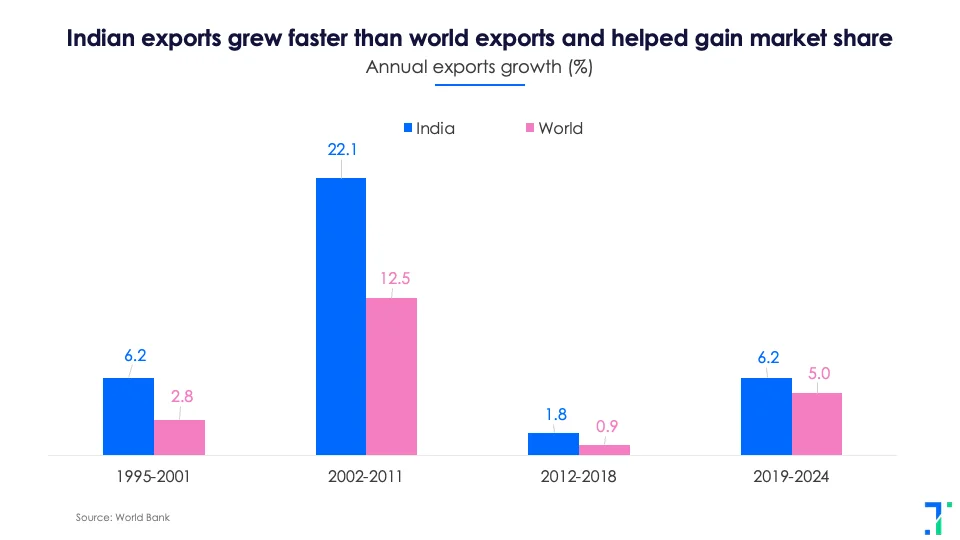

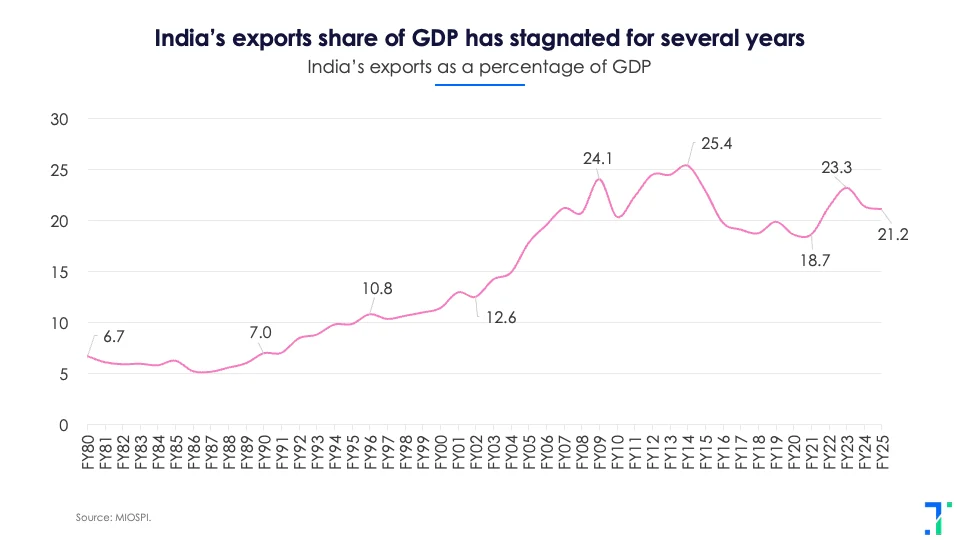

India had a track record of stellar export growth...till 2018

Growing in China's shadow, India's export story did not really make headlines. But from the early 1990s to 2018, India recorded the third-fastest export growth in the world, including in manufacturing, placing it alongside China and Vietnam.

India’s exports grew faster than global trade overall, helping it gain market share. Arvind Subramanian and Shoumitro Chatterjee note that the export outperformance came from real domestic progress, like productivity gains and more competitive Indian companies.

For nearly three decades, exports have been a core driver of India's growth, driven by companies in pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, chemicals, and modern services.

Structural bottlenecks have killed export momentum in recent years

Problems for India started after 2017, when a more protectionist central government placed higher tariffs on imports, impacting Indian companies, especially in the manufacturing and electronics space. These businesses depended heavily on global supply chains for inputs and raw materials.

Around the same time, demonetisation and the rollout of GST disrupted the informal sector and MSMEs, which form the backbone of many export industries.

Even as the government has tried to recently undo some of this damage, there are other structural problems. Logistics and power costs in India are among the highest in the world. Global competition is rising, with Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh also jockeying for exports market share.

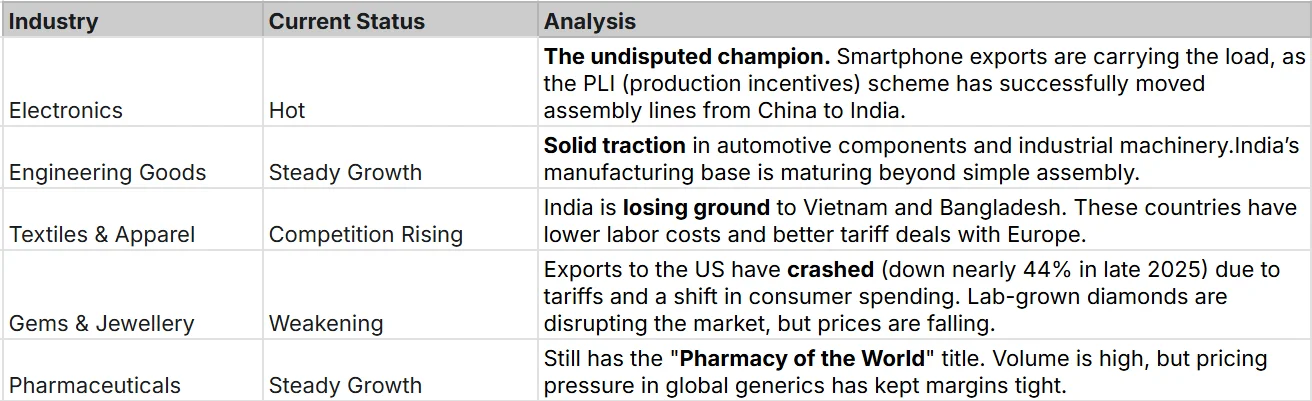

Some industries have boomed, while others faltered

When your report card only has A grades in 'attendance' and 'extra curriculars', you know you are going to be in trouble once you get home. India, as NITI Aayog’s Trade Watch notes, may be this kind of high scorer in exports, doing well in things that matter less.

India often has a large market share in products where global demand is weak, and too little share where demand is high. For instance, global demand for cotton is growing very slowly at just 1%, while India’s share in global cotton exports is more than 10%. But global defence trade has risen by over 15%: here India’s market share is less than 2%.

India is clearly not catching up fast enough with global shifts. While it is still big on cotton-based textiles, the demand has moved to manmade fibres. Countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam focused on manmade apparel and captured the market.

Even within pharmaceuticals, which is India's strong suit, the country excels at traditional generic medicines, where global demand is growing at a moderate pace. But the fastest growing part of the sector is in biologics and complex drugs like vaccines, where India has not gained significantly.

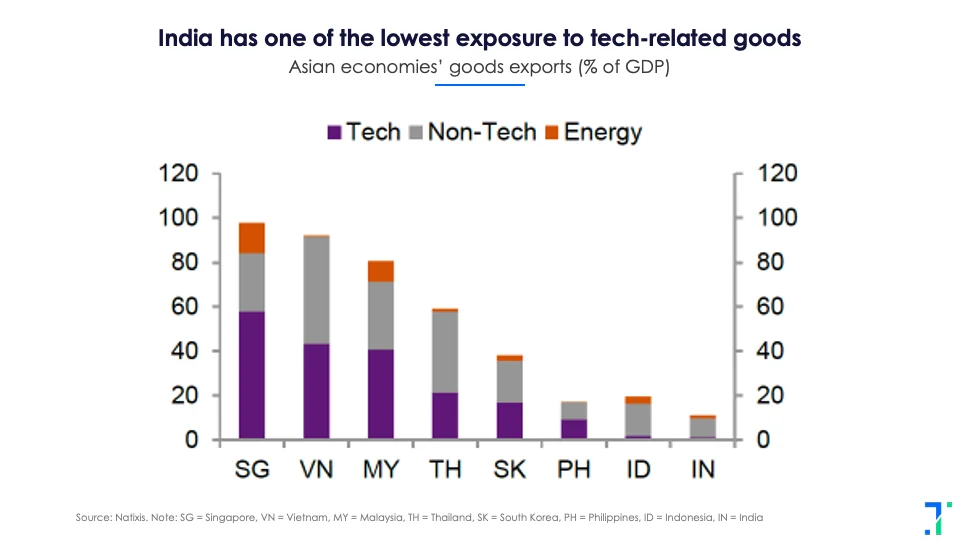

India also has the lowest exposure in Asia to a big boom sector - chips and electronics, or "tech goods". Countries like Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and South Korea have benefited here as demand has surged.

India's exports share of GDP has plateaued

There are some sectors where India has done impressively. India is now the top source of smartphone imports to the US, displacing China. It also remains a top pharma player, and engineering exports have held up.

When it comes to services exports, India’s main strength, nearly half comes from IT and telecom, Abhishek Bhandari of Nomura notes that here, AI has intensified pricing pressures and squeezed margins.

For now however, India's tech companies are integrating AI into their services. Growth is also being driven by Global Capability Centers (GCCs), which handle high-end R&D, and financial consulting. While global demand has been fluctuating, India’s services exports have been incredibly resilient.

But India needs to target a few booming export sectors aggressively to move the overall share of GDP higher. The share of exports in India's GDP has plateaued.

India is eyeing export growth just as China has woken up to the competition

India's success with smartphones has woken up the dragon, and it is reacting fast. China's counter-India efforts have become the single biggest strategic risk to India's export ambitions right now. Beijing has realized that rather than fighting India over finished goods, it can just squeeze the supply of raw materials needed to make them.

One is the solar squeeze. India is building solar panels at a record pace to meet its green energy targets. But China has restricted exports to India of wafers and key machinery. Prices for inputs like silver paste and cells spiked significantly in late 2025 because of this.

Another new bottleneck is China's blockade on EV batteries. China has imposed strict controls on Graphite exports, and you cannot make an EV battery anode without graphite. As India tries to jumpstart its own EV battery production, it is scrambling for alternative suppliers in Africa or Australia, which takes years to set up.

Most critically for India to target new booming sectors, China has restricted exports of Gallium and Germanium. These rare earths are needed for semiconductors, just as India’s semiconductor mission is getting off the ground.

While India is winning the battle in iPhones and automotive inputs, it is vulnerable across these emerging industries. The upcoming challenge may be less about "Make in India" than "Mine in India" (or find alternative mining sources) to break the China blockades.