Early December, usually a great time to travel, became a national nightmare this year across Indian airports. As IndiGo flights across the country were cancelled, the best laid plans fell apart. One student missed an engineering hackathon they were preparing for over the last several months. Many travellers missed exams, weddings, funerals, and long planned for international vacations. Suitcases disappeared into the black hole IndiGo called the "check-in counter", so people couldn't even just give up and go back home.

I escaped the chaos only because I was flying to Siliguri on a different airline, for my sixth wedding anniversary. But I saw the chaos at the terminal. The helpless ground staff stood there absorbing it all, one complaint at a time.

The silver lining, if we try to find one, is that people have now started talking about monopolies in Indian industry. India has several sectors where market power is concentrating very quickly into a few hands. If we don’t course-correct, it is very likely that the “IndiGo moment” will repeat elsewhere.

Competition is good, economists say. But the stock market doesn't reward it

Economists agree that competition in industries lowers prices, improves quality, and gives consumers more power. But investors actually prefer the opposite. The stock market loves companies with a “moat”: businesses that are so dominant, and with such high entry barriers that new players don't stand a chance. Warren Buffett for example, loves Coca-Cola, Moody’s and Apple, companies that have either absorbed or killed most of their competitors, and are hyper-dominant in their sectors.

Palantir's Peter Thiel openly says that "competition is for losers". Even the economist Joseph Schumpeter, who gave us the idea of “creative destruction” as new companies replace old ones, eventually concluded that monopolies might be capitalism’s natural end state.

Consumers want choice, but markets reward dominance.

India is seeing a concentration of power across sectors

To measure competition, economists use the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). A score below 1,500 means a competitive economy. Between 1,500 and 2,500 suggests moderate concentration. Anything above 2,500 is monopolistic and sets off alarm bells.

For the first time in over a decade, India has entered the “highly concentrated” danger zone. The HHI climbed from 1,980 in FY15 to 2,167 in FY20, and has crossed 2,532 in FY25.

Many Indian sectors now have a few companies with significant market power. Telecom for example, has become a slugfest between Bharti Airtel and Reliance Jio. Aviation has IndiGo and Air India dominating. In steel, four companies control more than half the market. And in cement, the Aditya Birla Group and Adani Group now have more than 50% of the market, and are still acquiring smaller players.

The concentration of market power gives companies pricing power, forcing consumers to pay more. It can also quickly reduce product options and quality.

This is just the tip of the iceberg

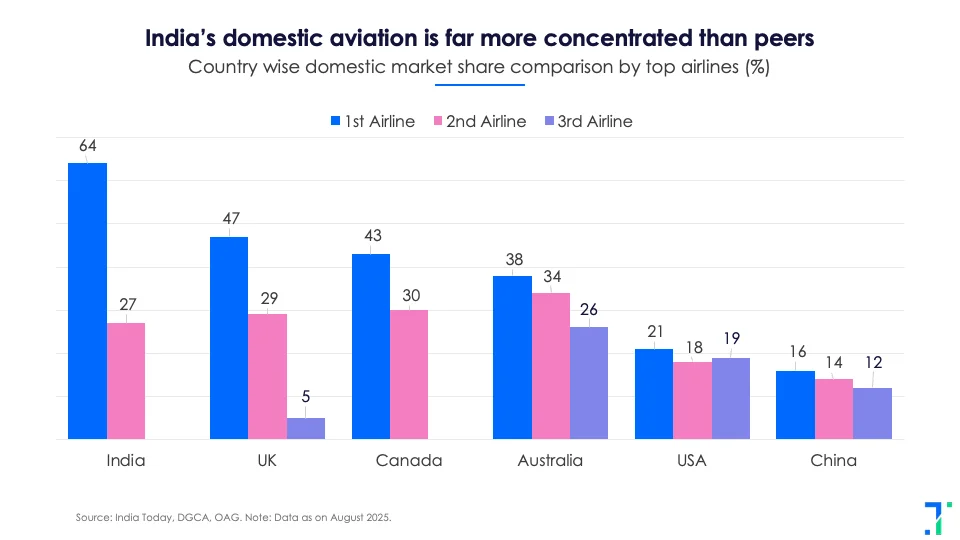

Few sectors in India show the problem better than aviation. India's domestic airfares were 43% higher in early 2024 than in 2019. In Asia, only Vietnam saw a bigger jump.

Two decades ago, India had close to ten airlines. Today, IndiGo and Air India control nearly 90% of the market. On many routes, there’s only one choice, usually IndiGo, which makes it the default price setter.

Airports are also increasingly controlled by just two private players, Adani and GMR, alongside the Airports Authority of India. Adani’s rapid expansion across airports, ports, and even lounges wiped out Dreamfolks’ once-dominant lounge business almost overnight.

History has a warning for us. The US spent the early 20th century breaking up Standard Oil, regulating railroad barons like Vanderbilt and Gould, and placing utilities under strict oversight. The US government cracked down after these monopolies raised prices, shut out competitors, and held entire regional markets in the US hostage.

India appears to be learning that lesson now, the hard way.

A global pattern

Globally, the pattern right now is 'bigger is better'. In the US, monopolies are making a comeback. Markups — the gap between price and cost —have jumped nearly 3X since the 1980s as industries have consolidated and companies feel free to increase prices.

For example, Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta, and BASF dominate global seeds and fertilisers. A few players control pharma generics and vaccines; Visa and Mastercard handle 80% of card payments, China’s Alipay and WeChat Pay control 95% of QR payments within China, and even India’s open UPI has created two dominant apps, PhonePe and Google Pay.

This pattern of fewer players, higher profits and weaker competition is now visible across many industries globally, pointing to more “winner-take-most” markets. We must worry about it as we, the consumers, are the ones paying a hefty price.

Should India dismantle its giants?

Former RBI Deputy Governor Viral Acharya has been sounding the alarm on monopolistic markets for years. His research shows that market concentration in India surged after 2015, driven by an industrial strategy favouring “national champions.”

By 2021, India’s biggest business groups controlled nearly 18% of assets in non-financial sectors, up from 10% in the early 1990s. Meanwhile, the next five largest groups saw their share halve. The dominant companies didn’t just crowd out small players, they squeezed out other large competitors as well.

One option, Acharya argues, is dismantling such groups where necessary. Recently, former Maharashtra CM Prithviraj Chavan and the President of the Federation of Indian Pilots, Captain C S Randhawa, urged the government to break IndiGo into at least two separate airlines.

China offers an instructive example. In the 1980s, it split its state airline into six entities. Three major airlines—Air China, China Eastern, and China Southern—emerged. Even today, together they control less than half the market.

Can India reverse this trend?

A monopoly, like a weed, is difficult to remove once it's entrenched. Dominant companies will fight, lobby, and pay the media to make their arguments for them. India needs a Competition Commission that can act before market power turns into abuse. The IndiGo episode should be a broader wake-up call.

Currently, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) intervenes only after abuse such as overpricing, blocking rivals, or distorting markets. In sectors like aviation, digital platforms, logistics, and infrastructure, that often means that they step in too late, after rivals are weakened and consumer choice has already shrunk.

The solution lies in reform. Some work has already begun. A Standing Committee report submitted in August backs ex-ante rules, stricter scrutiny of acquisitions, faster enforcement, fewer court delays, and a stronger CCI with better funding and expertise. It also calls for reviving a National Competition Policy, so that encouraging competition explicitly shapes government policy across sectors. Now it remains to be seen that if our current billionaire businessmen will let this happen.