Today’s Gen-Z gets triggered easily by events, complaining of “stress” and “anxiety”. But they’ve never known the collective tension India felt in the early 2000s, when Sachin Tendulkar entered the "nervous nineties" while batting. When his score hit that level, he would get jittery. Reaching 100 felt like an impossible crawl. We would watch the match through our fingers. Every ball was a heartbreak waiting to happen.

That same nervous energy is now in the currency markets.

At the start of the year, one dollar cost Rs 86. Today, it’s hit Rs 90. But unlike cricket where every Indian wanted Sachin to cross 100, the currency market is split. Importers are praying for levels of Rs 85–86. Exporters are hoping for Rs 100.

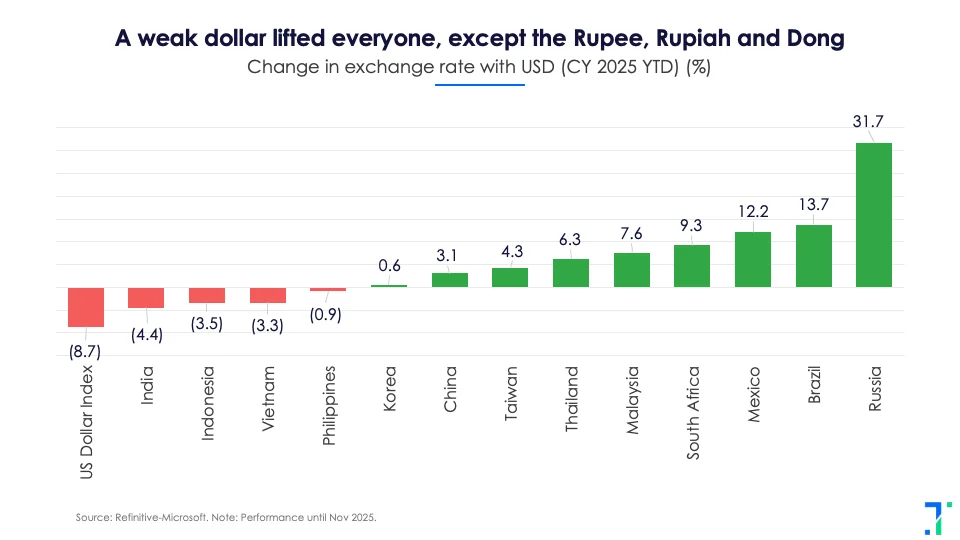

In the meantime, the Indian economy looks fantastic. GDP growth surprised on the upside, rising over 8% in the September quarter. Fundamentals are strong, and consumer demand is improving. The dollar is down 9%. By every traditional metric, this is not a moment when the rupee should be falling.

So what's going on? We dig a bit deeper.

“It’s just maths,” the RBI says. Really?

A big part of the RBI Governor's job is staying calm, at least outwardly, while everyone else gets stressed. Governor Sanjay Malhotra is good at that. When asked about the falling rupee by sweaty investors and journos, he gave a clean explanation: "inflation differentials drive long-term currency trends".

If India’s inflation is higher than America’s, the rupee has to depreciate over time to remain competitive. Historically, India’s inflation ran around 4% more than the US, and the rupee depreciated around 5% annually, almost in sync.

Malhotra has downplayed the rupee's depreciation as "just maths" and not a crisis. That’s the long term story. But there’s been a near-term change too, which starts with our central bank.

A big change in the RBI’s playbook

As we wrote earlier this year, the RBI kept the rupee unnaturally stable under former governor Shaktikanta Das. Nothing bounced, nothing swung. It was like “batting on a flat Melbourne pitch,” economist Arvind Subramanian says (a lot of people like cricket metaphors, it's not just me).

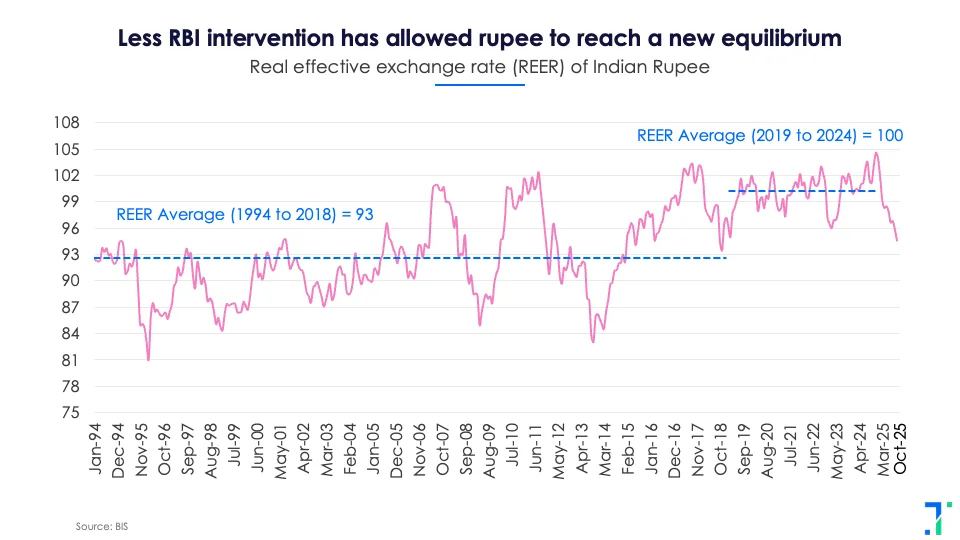

Under Das, this approach resulted in a stronger-than-expected rupee.

That has changed under Governor Malhotra, and the RBI is letting the rupee move more freely, stepping in only when volatility spikes. From July onwards for example, the RBI sold $30 billion to prevent a rapid slide after the trade shock and higher US tariffs, per Bloomberg. But over the last few weeks, traders say the RBI is once again hands-off.

The IMF has noticed the shift in policy as well. It has reclassified India’s currency regime from "stabilized" to the more flexible "crawl-like". While this means a weaker rupee in the short run, it is a massive boost to India's credibility. The global market sees a currency that is reflecting real dynamics, not artificial defence.

It also reduces speculation, builds trust, and frees the RBI to focus on domestic issues, while the exchange rate absorbs external shocks.

Enter Donald Trump

Some of the rupee’s pain can be traced back to Washington. President Trump’s reciprocal tariffs hit Indian goods hard. Analysts at the time expected a quick trade deal with the US, and the rupee even strengthened to Rs. 83–84 in May 2025.

Things have reversed since then:

-

By August, most Indian exports faced 50% tariffs

-

In September the US administration announced the H-1B visa fee hike

-

Combine this with $16B in equity outflows and a record $41B trade deficit in October, and the rupee became Asia’s worst performer.

Meanwhile, Taiwan, Korea and Malaysia, all with trade surpluses and lighter tariffs, saw their currencies appreciate.

Is 90 per dollar the new normal?

Many analysts thought that the worst was over for the rupee. Their year-end expectation was Rs 88.5 per dollar. Others, like RBL Bank’s Anitha Rangan, stayed cautious, and have been predicting Rs 90–92 as the RBI rebuilds reserves and exports stay weak.

But almost no one expects the rupee to improve beyond Rs 87–88 soon. For now, Rs 90 is the new normal. A Union Bank report added that geopolitics and tariffs will drive the rupee from here. Most experts agree that a US India trade deal is the fastest path to a stronger rupee.

No more photoshop: why a calibrated depreciation may be good for India

Countries like Vietnam, where exports are 90% of GDP, are letting their currencies weaken intentionally. It keeps their goods competitive despite US tariffs. China used the same strategy in 2019, during Donald Trump’s first term.

Vietnamese manufacturers like Pham Xuan Hong, who leads a group of clothing companies in Ho Chi Minh City, say a weaker dong is directly helping them survive higher costs and tariffs. Indian exporters feel similarly, that letting the rupee fall will help offset tariff pressure and protect margins.

Pankaj Chadha of the Engineering Export Promotion Council (EEPC) India says exporters are seeking Rs 103 per dollar — a big number, but the sentiment is not illogical.

Even JP Morgan’s Sajjid Chinoy suggests that letting the Indian rupee depreciate may be the smarter move. Besides a more credible exchange rate, a softer rupee lets exporters stay competitive until a trade deal happens. It also blunts China’s advantage — costlier Chinese imports mean that Indian firms are more competitive against Chinese products, and this would also narrow the trade deficit.

So maybe, we don't need to be that nervous. The central bank has shown a readiness to step in when speculation spikes. The fact is that the rupee no longer has a beauty filter on; we are in a currency regime that reflects reality more clearly.