Using maps in India can be quite an adventure, especially once you step outside the metros. Comedian Biswa Kalyan Rath once joked that Indian addresses are so confusing that it’s often necessary to stay on the phone and give the person moral support, as they try to find your house.

Enter MapmyIndia. In a world ruled by Google Maps, this player built a niche first with B2B and government projects, and later with its consumer app, Mappls. Users like how well it works in India's “gali–nukkad” neighbourhoods, where people will give you directions like, “turn left where the cow usually sits”.

But now, MapmyIndia is pushing for more: it’s asking the Indian government to require the Mappls app to be preloaded on all smartphones made under the Indian PLI scheme. The government hasn't made any announcements yet, but Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw called Mappls a "great swadeshi app", saying that the Indian Railways would soon sign an MoU with it.

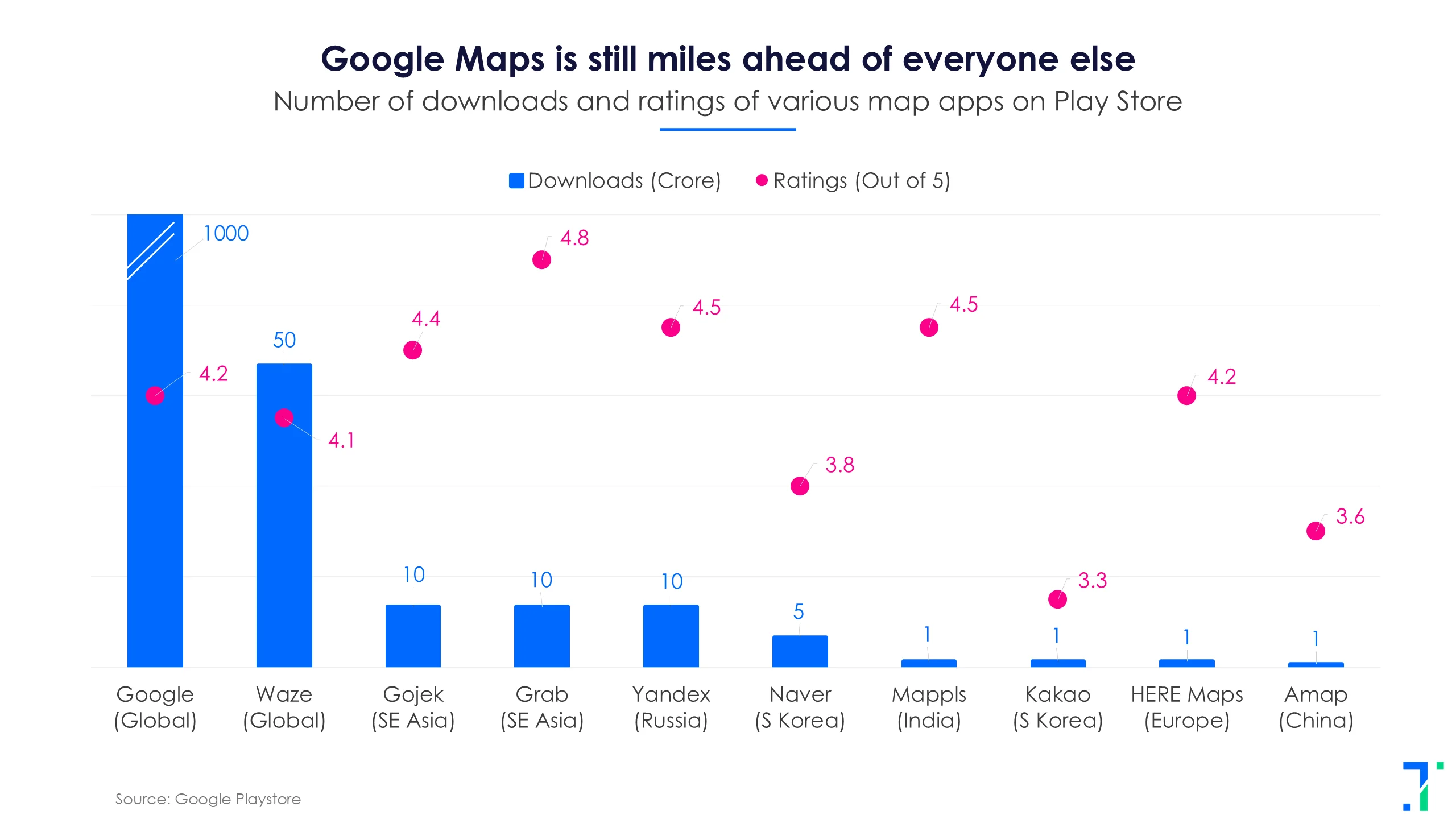

Google Maps rules the world, but alternatives are rising

Google Maps revolutionised how we travel, and proved the power of open ecosystems. But it also made governments outside the US worried about foreign control over geospatial data. Many countries pushed back in their own way. South Korea blocked foreign players, paving the way for local map apps like Naver and Kakao. Russia’s Yandex and 2GIS grew rapidly before falling under state control.

China went full firewall. Only homegrown map apps like Gaode and Baidu got full location data access, with government officials on company boards providing oversight.

Southeast Asia took a different route. Singapore's Grab built GrabMaps using driver data, while Indonesia's Gojek stuck with Google’s API. Both superapps have expanded across Asia while coexisting with Google — no bans, no censorship, no drama. When private companies compete without government bias, they innovate, attract users, and often go global.

India’s mapping scene is now heating up as well. After years of Google dominance, MapmyIndia and Ola Maps are rising challengers. The Indian market right now is more like Southeast Asia: dynamic and competitive.

A new wave of economic nationalism

But the political winds are shifting. After IT and Railways Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw praised MapmyIndia on X, the stock jumped 11%. A day later, Zoho’s Sridhar Vembu endorsed MapmyIndia even as several ministers began using Zoho’s office suite instead of Microsoft, as well as Arattai, the Zoho alternative to WhatsApp.

The message is clear: “Build Indian alternatives to global products, and the government will back you.” MapmyIndia’s own X feed proudly promotes itself as the “swadeshi” alternative.

There’s nothing wrong with national pride — it drives innovation and self-reliance. But when pride turns into political favoritism, are we devaluing consumer experience and a level playing field?

The confusion over imports versus GDP

Across the world, “imports are bad” is becoming a popular political view. The confusion comes in part, from that old economics formula:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M).

People think that when imports (M) rise, GDP falls. But that’s not true.

If you buy imports worth Rs 10,000, that’s counted under consumption (C), investment (I), or government spending (G). GDP measures what’s produced domestically, so we subtract imports to avoid double counting. Imports don’t shrink GDP — they just balance the books, and are essential for growth, supply chains, and customer choice.

Government efforts to “shield” domestic industries to boost local players usually end with less competition, higher prices for customers, and fewer choices. We tried that in the 60s and 70s and it didn’t go well. We ended up with low quality cars, TVs, refrigerators, a struggling economy, and fewer jobs.

Even where protectionism seems to have “worked,” it came with baggage. China and South Korea both built world-beating tech giants in a heavily protected domestic market — Alibaba, Tencent, Samsung, Hyundai. But with this, China’s market became heavily politicised through censorship, and the government is deeply entangled in the private sector, picking winners and losers. Korea’s close government–business ties led to power concentration and corruption. In both cases, government overreach stifled the market.

Learning from experience

Remember Koo, the “Indian Twitter”? It launched with a flurry of ministerial endorsements, then quietly shut down last year. “Made in India” can get people to try your product, but only real value keeps them there.

Or take RuPay, a more nuanced success story. The government’s subsidies helped it grow, but with those now being phased out, banks are facing Rs 500–600 crore losses and slowing new issuances. When UPI opens fully to all credit cards, will RuPay still lead? That's hard to say, especially with its limited global reach and modest rewards compared to Visa or Mastercard.

A better Indian model?

India already has a innovative growth playbook: our Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). We have cutting edge public infrastructure in Aadhaar, UPI, account aggregators, and ONDC. The government has built the rails on which the private sector is running the trains. That’s why PhonePe, Google Pay, and Paytm are competing with each other with world class products.

This is the opposite of preloading apps or tweeting government endorsements. Open platforms, clear rules, and healthy competition are far more powerful than protectionism.

Companies like Zoho and MapmyIndia are proof that Indian innovation can shine globally, without a government nudge. The path to scale isn’t through ministers’ tweets or “Made in India” stickers. It’s through great products, trust, and persistence.

Or, as Biswa might put it: “Maps that actually take you where you want to go.”