On July 11, the Chinese company Moonshot AI launched a new, cutting-edge AI model, Kimi K2. The scientific journal Nature called it ‘another DeepSeek moment’. But it did not get the DeepSeek buzz, and barely anyone in the general public noticed.

Many recent China news stories, in fact, haven’t caught much media attention. ByteDance for instance, the makers of TikTok, has quietly beaten Meta to become the world’s largest social media company by revenue in the first quarter of this year. China has also announced that it will spend $8.5 billion to boost new start-ups in AI.

Governments are watching -- and they are worried. At the G7 summit earlier this month, German Finance Minister Lars Klingbell said that they are looking at how to limit China's economic power. "There are concerns that the G-7 countries are losing influence," he said.

As China becomes increasingly dominant in tech innovation and trade, countries see their domestic economy and industry is under threat. They may have good reasons to worry. Many sci-fi films - from Bladerunner to Terminator - are based in the US. But the future may very well be Chinese.

China is getting closer to building a James Bond car

Remember the cars of the fictional British spy? James Bond has cars with missile launchers and ejector seats, that can even run underwater.

The new launches at the Shanghai Auto Show this year felt like something out of a Bond flick. For instance, the Nio ET9 can turn into a full-fledged 5D theatre, with shaking seats, moving suspension, and AC that syncs with movie action scenes. I would be very interested to find out what happens to that car while playing a Rohit Shetty film.

BYD is attracting travel vloggers with inbuilt drone cameras for its cars. Nio’s Onvo L60 has a fridge, while Ora has added thoughtful touches for women like menstrual pain relief and a built-in emergency alert.

As driving and car-charging tech became standard, automakers are in a race to be different by adding other software with more capabilities. The advantage now is all in the software, which is why such cars are called Software-Defined Vehicles (SDVs).

Software-first approach gives Chinese cars the edge

Consider Xiaomi. It has launched an electric car in 2024 that runs on HyperOS — the same system used in its phones and gadgets. The car becomes just another machine in the company's Mi ecosystem, which also includes robot mops, smart watches and lamps.

Xiaomi cars pack premium features like a Tesla — LiDAR, 800V charging, air suspension — but keeps prices low by cutting margins. AI tech powers everything from self-driving to real-time defect detection. It’s a software-first car compared to Tesla, which is a car with a tech edge.

While Tesla still leads the EV category in the Wards Intelligence rankings for both 2023 and 2024, the leaderboard is shifting fast. In 2023, Tesla was followed by Lucid (US), Rivian (US), Nio (China), and Polestar (Sweden).

But in 2024, Chinese players Nio, Xiaomi and Xpeng occupied second, third and fourth positions, respectively, pushing Rivian down to fifth. Xiaomi grabbed the third place in its first year making electric vehicles. This is a competitor to fear.

The Squid Game - survival of the fittest - in the auto sector

State support and smart engineers have played a big role in China's tech rise. But competition is the X factor here.

The pressure in China's market is brutal. Out of nearly 500 new electric vehicle makers in 2018, over 90% have failed, and another 80% are expected to disappear in the next five years. This Darwinian race has left only the most innovative and financially smart companies still standing.

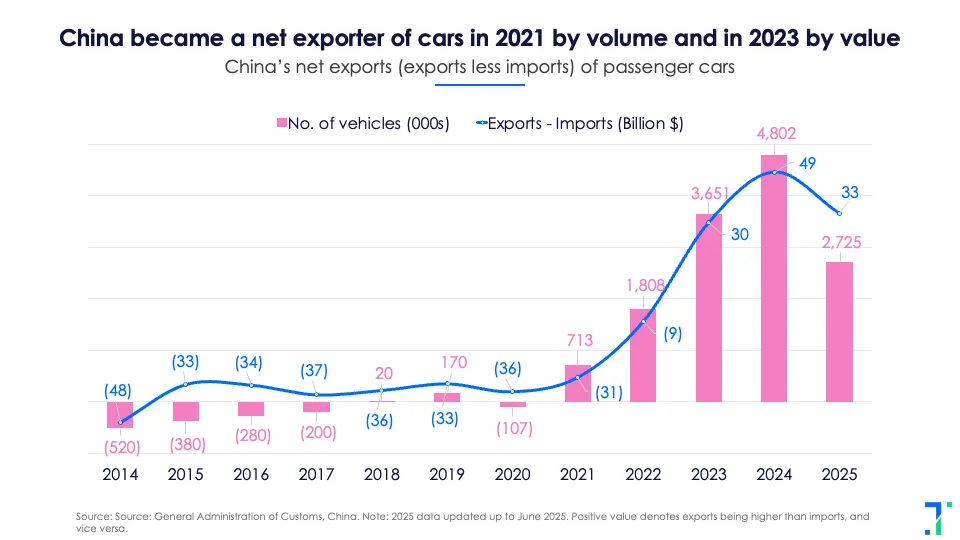

This approach has killed many entrepreneurial dreams in China, but it has helped the economy and people. China became a net exporter of cars in the last few years, from being a net importer in 2020. And average EV prices in China are down by 14% since 2023.

One company, many different industries

Right now, BYD is busy building the world’s largest battery storage facility of 12.5GWh in Saudi Arabia. It is applying all its EV knowhow to other industries. It is using its signature blade battery across industries to make energy storage systems, and borrowing the lithium iron phosphate chemistry and ceramic insulation tech from its cars.

Many components used in EVs — like batteries, motors, power electronics, and software — are also used in drones, robots, and home appliances. This modular approach to manufacturing is known as the “Lego block” structure. The knowledge from making smartphones and cars is now being used in drones and AI-driven gadgets.

China's electric tech stack is powering new products across the economy

Electric batteries, motors, power electronics and computing are the main drivers of innovation in China right now. It's being called China’s ‘electric tech stack’.

Two main aspects have helped them develop this stack. The first is domestic control over the full value chain. From mining lithium, cobalt, and rare earths to refining, battery production, and final assembly, Chinese firms can develop vertical integration faster, fix supply chain bottlenecks, reduce costs and launch products quickly.

Second is the location. In places like Shenzhen, suppliers, engineers, and factories operate next to each other. Engineers can walk from the design studio to the assembly line, solving problems quickly. Similarly, an EV maker in Shanghai can get all its components in just four hours from Changzhou, a place that handles 31 of the 32 steps in battery production, covering 97% of the value chain.

It's a bird...it's a car? China's push for a flying economy

If you can build a car, why not a flying one? Backed by a mature EV supply chain, Chinese companies like Ehang, XPeng, Autoflight, and Geely’s AeroFugia are building eVTOLs (electric vertical takeoff and landing vehicles) using the same battery and technology.

China is pushing for a low-altitude flying economy, with air taxis, drone deliveries, etc., with a roadmap that includes pilot licenses, aerial tolls, and eVTOL test zones.

At the centre of it all is DJI, which commands over 70% of the global drone market. With over 2.2 million civilian drones flying across China, their use in warfare has drawn scrutiny. Beijing is also ramping up drone production for defence, including a mosquito-sized surveillance drone that’s light, silent, and controlled via smartphone.

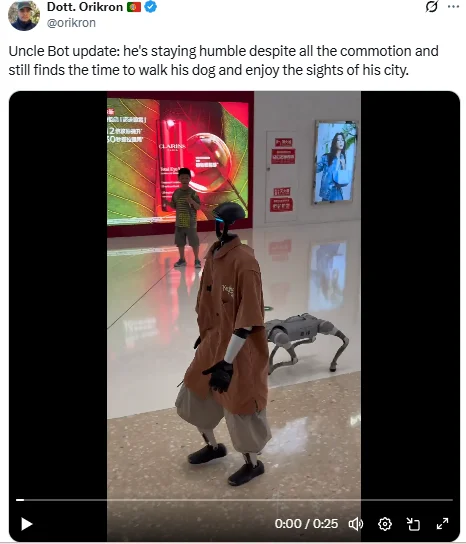

Are robots going mainstream?

Unitree's G1 robot, available for online purchase, has recently gone viral online and nicknamed 'Uncle Bot' for its natural movement and behavior. Many Chinese tech players including car makers are leaning into robotics.

Robotics and electric cars share deep technological overlap — both rely on sensors, batteries, motors, and advanced algorithms. Around 70% of components are interchangeable between these sectors. That’s why automakers like BYD, Xiaomi, SAIC, GAC, XPeng, and Huawei are entering robotics.

XPeng’s Iron Robot, for instance, uses the navigation systems of autonomous vehicles. GAC Group’s GoMate robot runs on EV battery packs.

China has over 230,000 robotics firms, supported by a roadmap to mass-produce humanoid robots and build a $43 billion industry by 2035. XPeng’s chairman urged an EV-style policy support for robots, predicting similar explosive growth.

AI investment is much lower in China compared to the US

AI is poised to be the main computing agent in all applications, products, and services. The government is driving AI investments through labs, data centres, and partnerships with firms like Alibaba and ByteDance. It is going to invest $56 billion out of a total $84–98 billion projected in 2025.

This is opposite of the US, where almost all investment is private sector-driven. For instance, AI capex by US tech Big 4 (Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Meta) is estimated to be $302 billion in 2025, whereas for China’s Big 4 (Alibaba, Baidu, ByteDance, and Tencent) it is at $51 billion. Absolute spending in the US is almost six times higher than China.

Will this tech stack help China dominate the world?

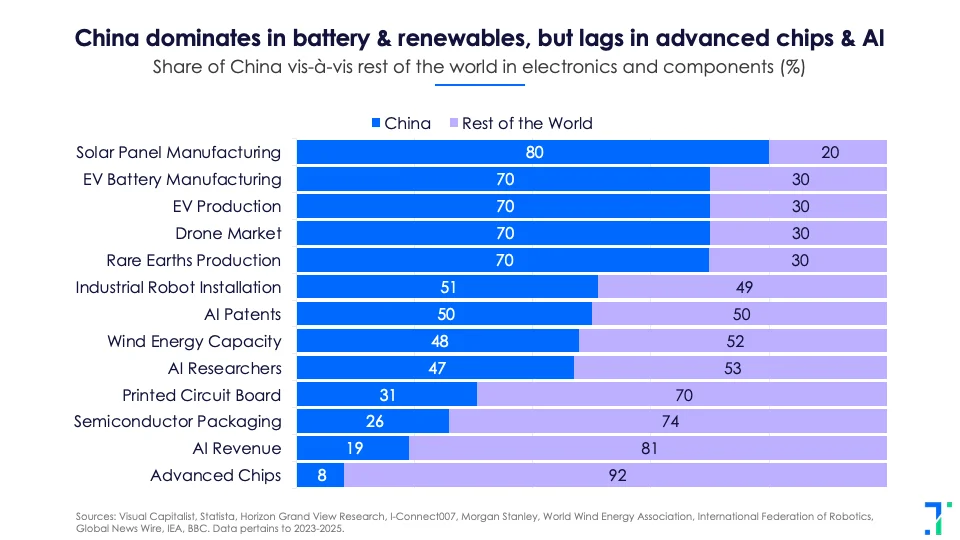

China’s manufacturing scale is reshaping global markets. It’s a leader in many areas like batteries, solar panels, rare earth production, drones and robotics. Its dominance gives it geopolitical leverage, as recently seen in the case of rare earths.

China-made products are no longer inferior to their Western counterparts in terms of quality and functionality. They are also usually 20–40% cheaper. That forces countries to impose tariffs and curb trade. But that has not stopped innovation in China.

For instance, Nvidia was asked not to export chips to China by the US government, creating a shortage of chips in China. Nio, which relied on Nvidia chips earlier, now uses its own ET9 chips. “It’s precisely the shortage of semiconductors that is leading China to develop their own faster,” says Frank Bournois, dean of the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai.

Still, challenges remain. Global firms are diversifying supply chains, while China faces a slowing economy, youth unemployment, ageing demographics, and a post-Covid trust deficit — making global dominance harder. But the Chinese government is ambitious, and so far, its efforts have been paying off.